Empty set

In mathematics, and more specifically set theory, the empty set is the unique set having no elements; its size or cardinality (count of elements in a set) is zero. Some axiomatic set theories assure that the empty set exists by including an axiom of empty set; in other theories, its existence can be deduced. Many possible properties of sets are trivially true for the empty set.

Null set was once a common synonym for "empty set", but is now a technical term in measure theory.

Contents |

Notation

Common notations for the empty set include "{}," " ", and "

", and " ". The latter two symbols were introduced by the Bourbaki group (specifically André Weil) in 1939, inspired by the letter Ø in the Danish and Norwegian alphabet (and not related in any way to the Greek letter Φ).[1] Other notations for the empty set include "Λ" and "0"[2]

". The latter two symbols were introduced by the Bourbaki group (specifically André Weil) in 1939, inspired by the letter Ø in the Danish and Norwegian alphabet (and not related in any way to the Greek letter Φ).[1] Other notations for the empty set include "Λ" and "0"[2]

The empty-set symbol ∅ is found at Unicode point U+2205.[3] In TeX, it is coded as \emptyset or \varnothing.

Properties

By the principle of extensionality, two sets are equal if they have the same elements; therefore there can be only one set with no elements. Hence there is but one empty set, and we speak of "the empty set" rather than "an empty set".

The mathematical symbols employed below are explained here.

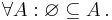

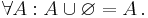

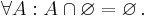

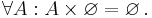

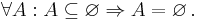

For any set A:

- The empty set is a subset of A:

- The union of A with the empty set is A:

- The intersection of A with the empty set is the empty set:

- The Cartesian product of A and the empty set is empty:

The empty set has the following properties:

- Its only subset is the empty set itself:

- The power set of the empty set is a set containing only the empty set:

- Its number of elements (that is, its cardinality) is zero:

The connection between the empty set and zero goes further, however: in the standard set-theoretic definition of natural numbers, we use sets to model the natural numbers. In this context, zero is modelled by the empty set.

For any property:

- For every element of

the property holds (vacuous truth);

the property holds (vacuous truth); - There is no element of

for which the property holds.

for which the property holds.

Conversely, if for some property and some set V, the following two statements hold:

- For every element of V the property holds;

- There is no element of V for which the property holds,

- then

.

.

By the definition of subset, the empty set is a subset of any set A, as every element x of  belongs to A. If it is not true that every element of

belongs to A. If it is not true that every element of  is in A, there must be at least one element of

is in A, there must be at least one element of  that is not present in A. Since there are no elements of

that is not present in A. Since there are no elements of  at all, there is no element of

at all, there is no element of  that is not in A. Hence every element of

that is not in A. Hence every element of  is in A, and

is in A, and  is a subset of A. Any statement that begins "for every element of

is a subset of A. Any statement that begins "for every element of  " is not making any substantive claim; it is a vacuous truth. This is often paraphrased as "everything is true of the elements of the empty set."

" is not making any substantive claim; it is a vacuous truth. This is often paraphrased as "everything is true of the elements of the empty set."

Operations on the empty set

Operations performed on the empty set (as a set of things to be operated upon) are unusual. For example, the sum of the elements of the empty set is zero, but the product of the elements of the empty set is one (see empty product). Ultimately, the results of these operations say more about the operation in question than about the empty set. For instance, zero is the identity element for addition, and one is the identity element for multiplication.

Mathematics

Extended real numbers

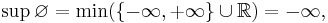

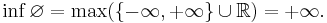

Since the empty set has no members, when it is considered as a subset of any ordered set, then every member of that set will be an upper bound and lower bound for the empty set. For example, when considered as a subset of the real numbers, with its usual ordering, represented by the real number line, every real number is both an upper and lower bound for the empty set.[4] When considered as a subset of the extended reals formed by adding two "numbers" or "points" to the real numbers, namely negative infinity, denoted  which is defined to be less than every other extended real number, and positive infinity, denoted

which is defined to be less than every other extended real number, and positive infinity, denoted  which is defined to be greater than every other extended real number, then:

which is defined to be greater than every other extended real number, then:

and

That is, the least upper bound (sup or supremum) of the empty set is negative infinity, while the greatest lower bound (inf or infimum) is positive infinity. By analogy with the above, in the domain of the extended reals, negative infinity is the identity element for the maximum and supremum operators, while positive infinity is the identity element for minimum and infimum.

Topology

Considered as a subset of the real number line (or more generally any topological space), the empty set is both closed and open; it is an example of a "clopen" set. All its boundary points (of which there are none) are in the empty set, and the set is therefore closed; while for every one of its points (of which there are again none), there is an open neighbourhood in the empty set, and the set is therefore open. Moreover, the empty set is a compact set by the fact that every finite set is compact.

The closure of the empty set is empty. This is known as "preservation of nullary unions."

Category theory

If A is a set, then there exists precisely one function f from {} to A, the empty function. As a result, the empty set is the unique initial object of the category of sets and functions.

The empty set can be turned into a topological space, called the empty space, in just one way: by defining the empty set to be open. This empty topological space is the unique initial object in the category of topological spaces with continuous maps.

Questioned existence

Axiomatic set theory

In Zermelo set theory, the existence of the empty set is assured by the axiom of empty set, and its uniqueness follows from the axiom of extensionality. However, the axiom of empty set can be shown redundant in either of two ways:

- A logic such that provability and truth hold for both empty as well as nonempty domains is called a free logic. Set theory is almost never formulated with free logic as its background logic; hence many theorems of set theory are valid only if the domain of discourse is nonempty. Canonical axiomatic set theory assumes that everything in the (nonempty) domain is a set. Therefore at least one set exists; call it A. By the axiom schema of separation (a theorem in some theories), the set B = {x | x∈A ∧ x ≠ x} exists and, having no members, is the empty set;

- The axiom of infinity, included in all mathematically interesting axiomatic set theories, not only asserts the existence of an infinite set I (from which B in the preceding paragraph may be constructed), but typically requires that the empty set be a member of I.

Philosophical issues

While the empty set is a standard and widely accepted mathematical concept, it remains an ontological curiosity, whose meaning and usefulness are debated by philosophers and logicians.

The empty set is not the same thing as nothing; rather, it is a set with nothing inside it and a set is always something. This issue can be overcome by viewing a set as a bag—an empty bag undoubtedly still exists. Darling (2004) explains that the empty set is not nothing, but rather "the set of all triangles with four sides, the set of all numbers that are bigger than nine but smaller than eight, and the set of all opening moves in chess that involve a king."[5]

The popular syllogism

- Nothing is better than eternal happiness; a ham sandwich is better than nothing; therefore, a ham sandwich is better than eternal happiness

is often used to demonstrate the philosophical relation between the concept of nothing and the empty set. Darling writes that the contrast can be seen by rewriting the statements "Nothing is better than eternal happiness" and "[A] ham sandwich is better than nothing" in a mathematical tone. According to Darling, the former is equivalent to "The set of all things that are better than eternal happiness is  " and the latter to "The set {ham sandwich} is better than the set

" and the latter to "The set {ham sandwich} is better than the set  ". It is noted that the first compares elements of sets, while the second compares the sets themselves.[5]

". It is noted that the first compares elements of sets, while the second compares the sets themselves.[5]

Jonathan Lowe argues that while the empty set:

- "...was undoubtedly an important landmark in the history of mathematics, … we should not assume that its utility in calculation is dependent upon its actually denoting some object."

it is also the case that:

- "All that we are ever informed about the empty set is that it (1) is a set, (2) has no members, and (3) is unique amongst sets in having no members. However, there are very many things that 'have no members', in the set-theoretical sense—namely, all non-sets. It is perfectly clear why these things have no members, for they are not sets. What is unclear is how there can be, uniquely amongst sets, a set which has no members. We cannot conjure such an entity into existence by mere stipulation."

George Boolos argued that much of what has been heretofore obtained by set theory can just as easily be obtained by plural quantification over individuals, without reifying sets as singular entities having other entities as members.[6]

The empty set is a crucial part of the philosophy of Alain Badiou. For Badiou, the empty set, referred to as "the void," is considered to be "the proper name of being" and thus the foundational material of ontology.

See also

Notes

- ^ Earliest Uses of Symbols of Set Theory and Logic.

- ^ John B. Conway, Functions of One Complex Variable, 2nd ed. P. 12.

- ^ Unicode Standard 5.2

- ^ Bruckner, A.N., Bruckner, J.B., and Thomson, B.S., 2008. Elementary Real Analysis, 2nd ed. Prentice Hall. P. 9.

- ^ a b D. J. Darling (2004). The universal book of mathematics. John Wiley and Sons. p. 106. ISBN 0471270474.

- ^ *George Boolos, 1984, "To be is to be the value of a variable," The Journal of Philosophy 91: 430–49. Reprinted in his 1998 Logic, Logic and Logic (Richard Jeffrey, and Burgess, J., eds.) Harvard Univ. Press: 54–72.

References

- Paul Halmos, Naive set theory. Princeton, NJ: D. Van Nostrand Company, 1960. Reprinted by Springer-Verlag, New York, 1974. ISBN 0-387-90092-6 (Springer-Verlag edition).

- Jech, Thomas, 2003. Set Theory: The Third Millennium Edition, Revised and Expanded. Springer. ISBN 3-540-44085-2.